The book in three sentences

Bad customer conversations aren't failure of honesty but failure of process - it's your responsibility to ask questions that reveal the truth, not their responsibility to tell it to you.

Talk about their life instead of your idea - focus on specifics from the past rather than opinions about the future.

Every conversation should have at least one question that could destroy your currently imagined business - you want the truth, not a gold star.

I first picked up this book in 2022. I was studying User Research in Reforge, and I kept stumbling upon references during conversations and podcasts. I came back to this read in 2024 as I went deeper into customer interviews for building Products, and I have three takeaways to share:

The value of leading with questions

Preparing for conversations and digging deeper

Product vs Market risk, when conversations are useful

Here's one example back from 2022, crossing references from The Mom Test.

Lead with questions

During my technology career, I cataloged many enlightening questions that helped me navigate life and business. It became my own playbook called the questions bible.

When I started the process, none of the cool AI creative tools were available. Asking the right questions or structuring the right prompts has never been so critical.

To me, the objective of reading this book is to have better conversations because learning how to do this well gives you the building blocks for everything else.

Now, what does that have to do with moms? Simple, the system is designed to generate sanity-check questions for your business ideas, so that not even mom can lie to you if they're terrible.

Preparing for conversations

Rob's framework reminds me of what I have seen from Reforge Effective Customer Conversations, and I see myself returning to these steps when planning a new chat.

Vision — half-sentence of how you’re making the world better

Framing — where you’re at and what you’re looking for

Weakness — where you’re stuck and how you can be helped

Pedestal — show that they, in particular, can provide that help

Ask — ask for help

Here's a real example from a customer interview last week. I'm focused on building CMS capabilities for a large editorial team:

I'm trying to solve the inefficiencies we have with batch content scheduling. This process should be easier, with a maximum of three clicks from the article view to a calendar view with the visual confirmation of future schedules. (Vision)

We started prototyping right now, and we are not ready to share low-fidelity wireframes. (Framing)

I know your team today has alternative ways to cope with the current functionalities, but I can't reproduce the ins and outs of your ways of working, and I can't build without your perspective. (Weakness)

You have a lot of experience in the business and have been around longer than I have. (Pedestal)

Could you guide me through the existing workflow and help me identify the areas where we are hacking things? (Ask)

Digging into feature requests

Moving from experimentation to product, the biggest shift in my daily language was how often I started asking, "Can you give me an example?"

I noticed that in most cases, the request is not serious enough to get the person to provide a good example.

Apart from the elegant pushback of asking for examples, these are my top five questions when digging into feature requests straight out of The Mom Test.

How do you currently solve {{use case}}?

How much does it cost to do so? And how much time does it take?

Talk me through the last time that happened; give me an example.

How are you dealing with it now? What else have you tried?

What makes you want that? What would that let you do?

Product vs Market risk

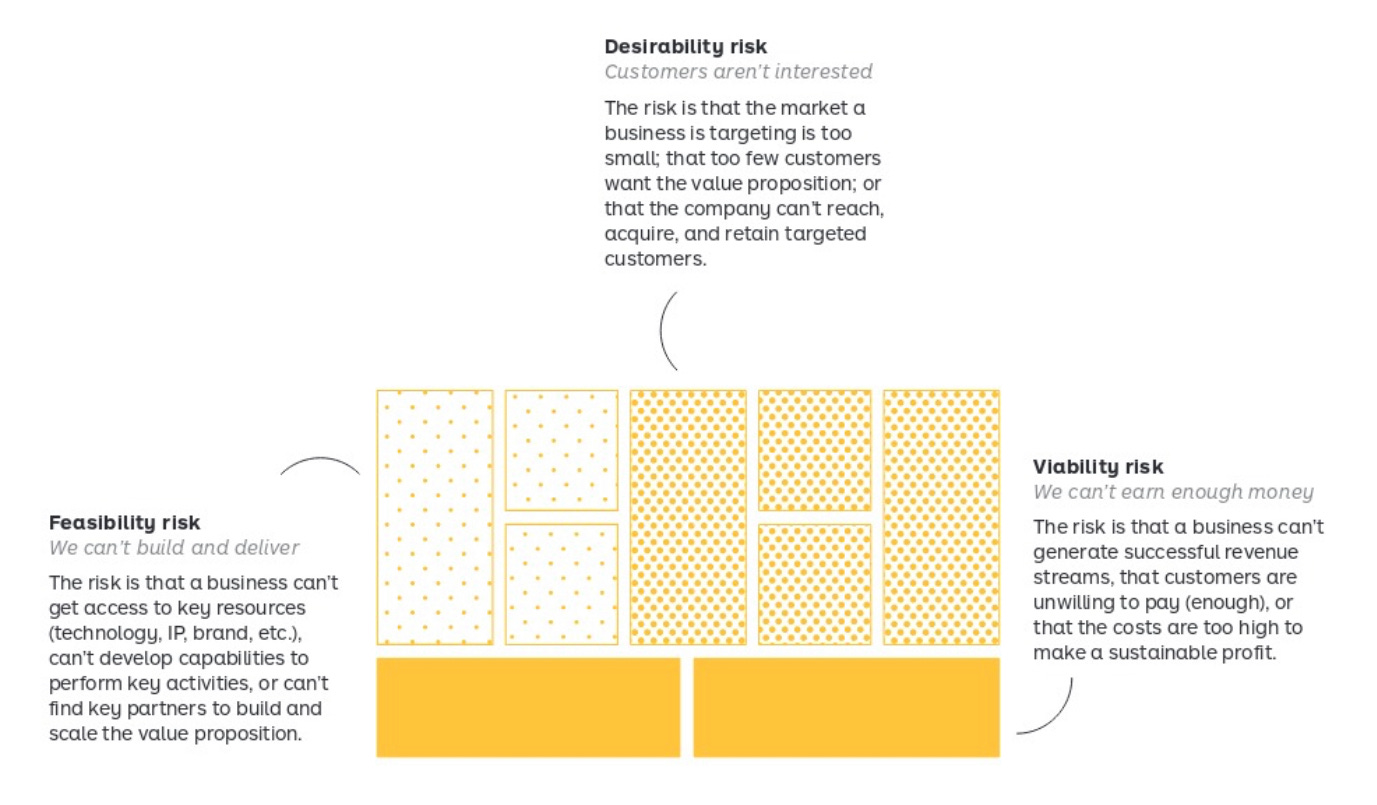

This is great thinking for Product people; it's very well connected to how Strategyzer perceives the business model canvas and how Marty Cagan comments on the Product Discipline in his book Empowered.

Rob brings attention to two risks:

Product risk: Can I build it? Can I grow it?

Customer/market risk: Do they want it? Will they pay me? Are there lots of them?

I like to think of Market risk as the desirability section of the business canvas, where the value proposition, distribution channels, and customer segments are scrutinized. On the other hand, Feasibility risk is concerned with key partnerships, resources, and activities.

If you have significant product risk (as opposed to pure market risk), you won’t be able to prove as much of your business through conversations alone. Conversations give you a starting point, but you’ll have to start building the product earlier and with less certainty than if you had pure market risk.

The person who asks a question is a fool for a minute.

The person who does not ask is a fool for life.

— Confucius